Nawa to Onna (1970): Rope, Women, and the Birth of a Visual Trilogy

In 1970, at a pivotal moment in the evolution of Japanese S&M culture, a small but remarkably coherent group of books appeared under a single title: Nawa to Onna — Rope and Woman.

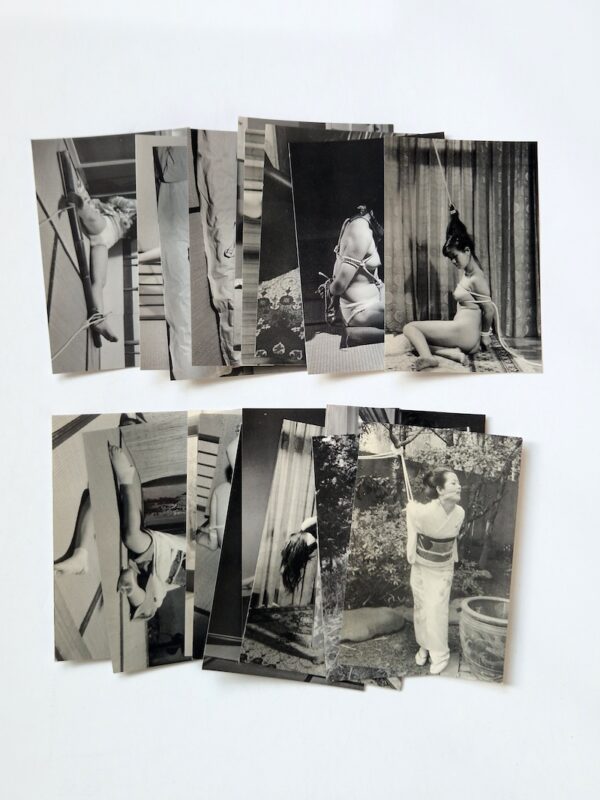

Issued by Misaki Shobo, the project took the form of three volumes released almost simultaneously: one illustrated anthology and two photographic books. Together, they form what can only be understood as a conceptual trilogy, uniting drawing, photography, and kinbaku practice within a shared editorial vision.

At first glance, these books may appear as isolated genre publications. A closer reading, however, reveals something far rarer: a moment when illustration, physical rope work, and editorial intent converged to define a visual language that would soon migrate from the printed page to cinema.

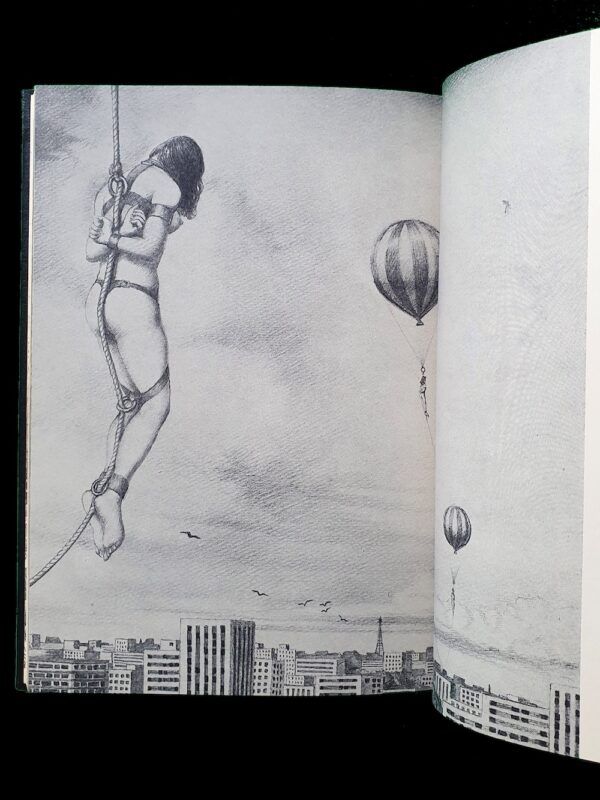

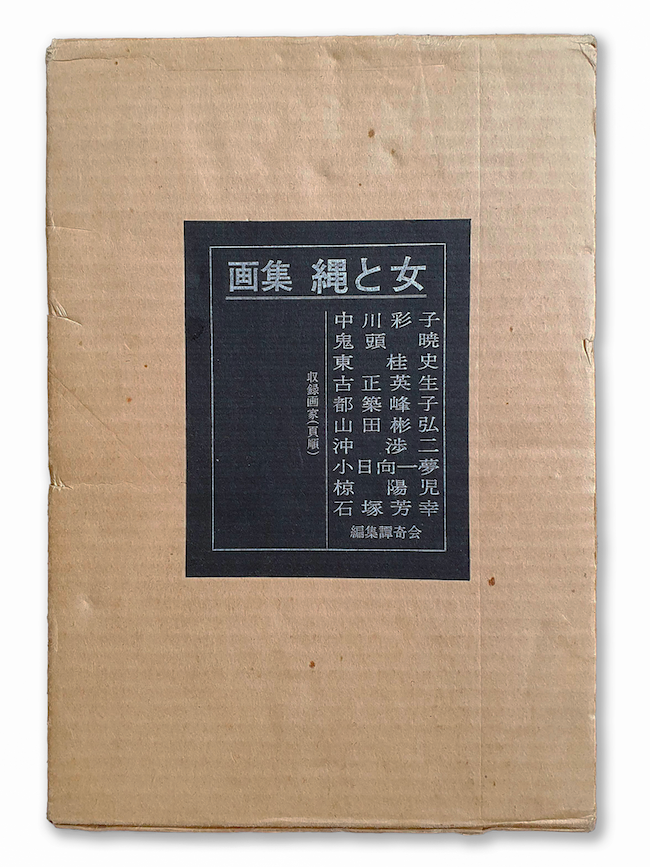

The Illustrated Core: Gashū Nawa to Onna

The first volume, 画集『縄と女』 (Gashū Nawa to Onna), was published on December 10, 1970.

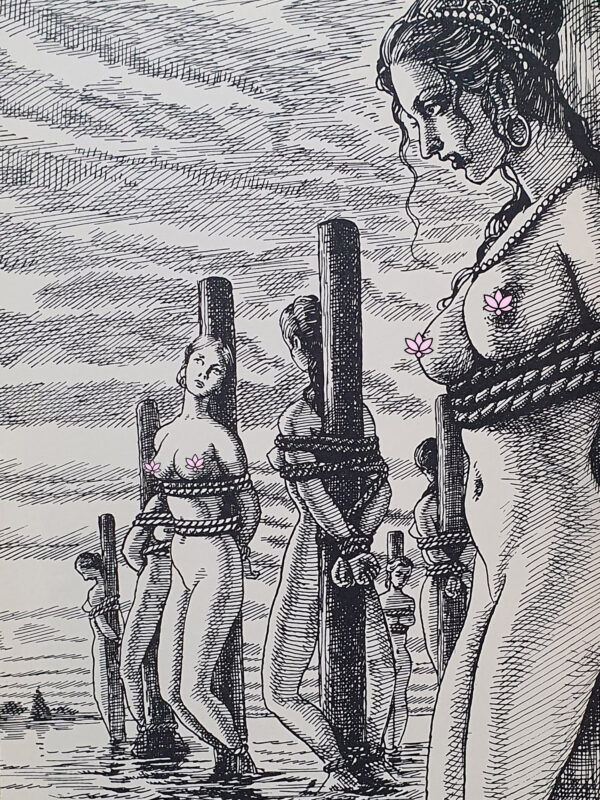

It is an illustrated anthology bringing together many of the most active S&M artists of the postwar period. Their work had already shaped magazines such as Uramado, Kitan Club, Fuzoku Sōshi, and Suspense Magazine.

Among the contributors are Ayako Nakagawa (Kazutomo Fujino), Akira Kitō, Shoji Oki, Hideo Furushō, Yoshiyuki Ishizuka, Mineko Tsuzuki (alias of Shizuo Yagi), and others. Many worked under pen names, with careers spread across shifting editorial contexts.

The anthology was curated by Yoji Muku, one of the most distinctive figures of the era.

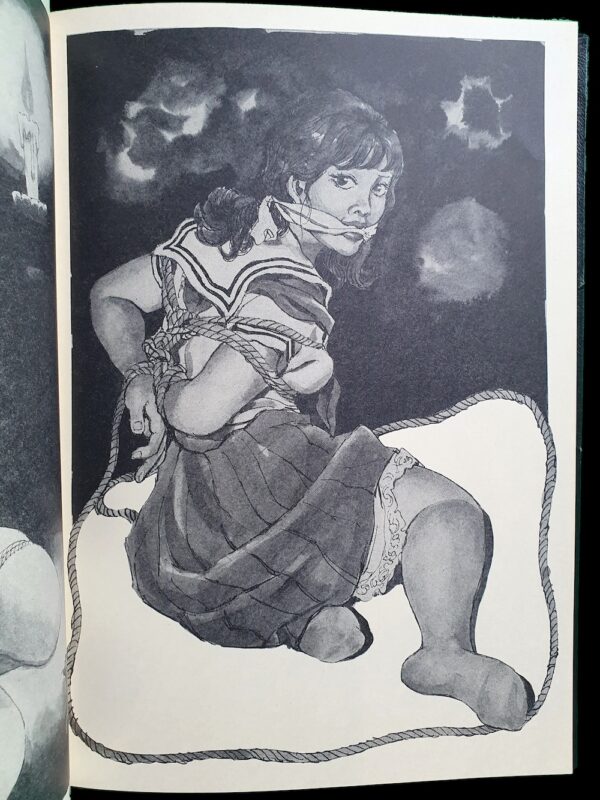

Muku was not merely an illustrator. He operated at the intersection of drawing, photography, and editorial work. He entered the SM world through magazines and developed a personal fixation on rope imagery. He became one of the most controversial figures in Japanese SM illustration for drawings that explicitly fixated on extreme domination and figures represented as very young, sometimes pre-adult in appearance.

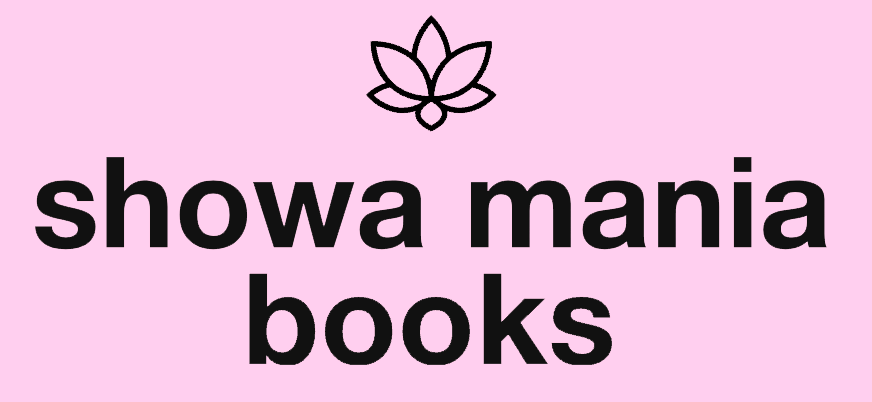

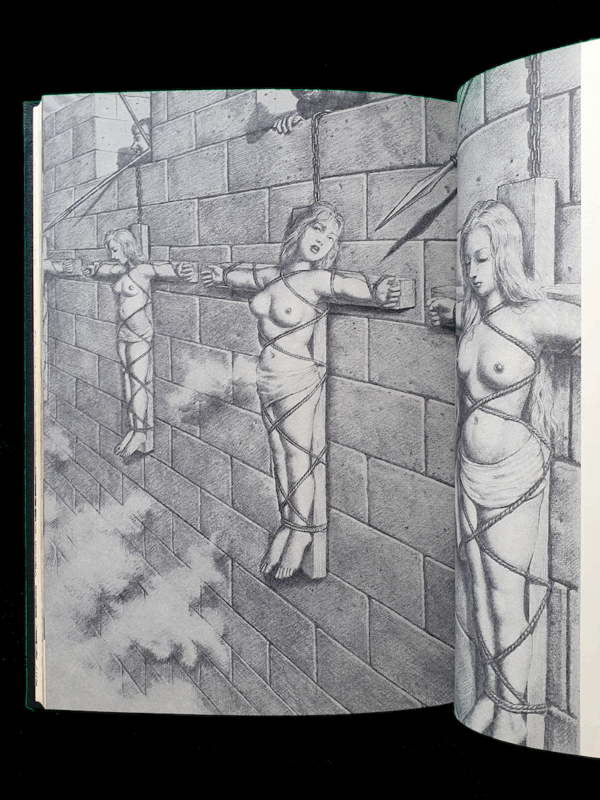

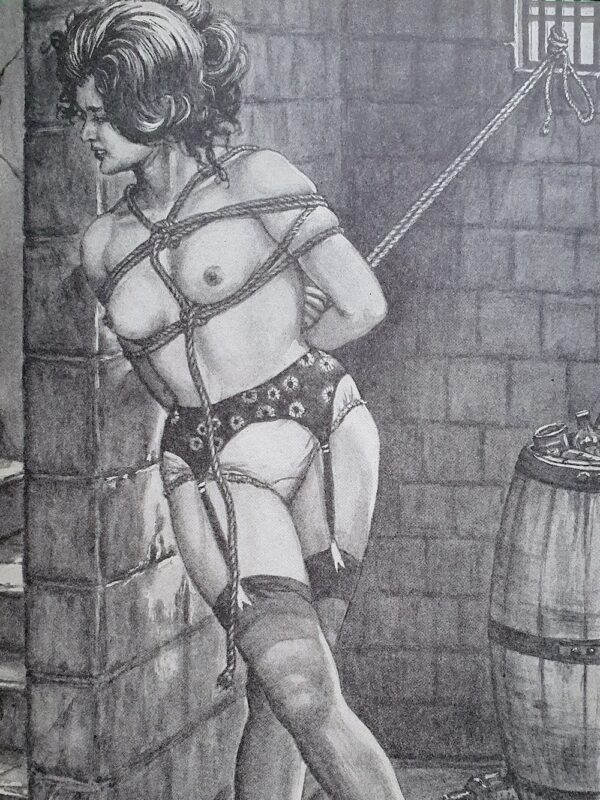

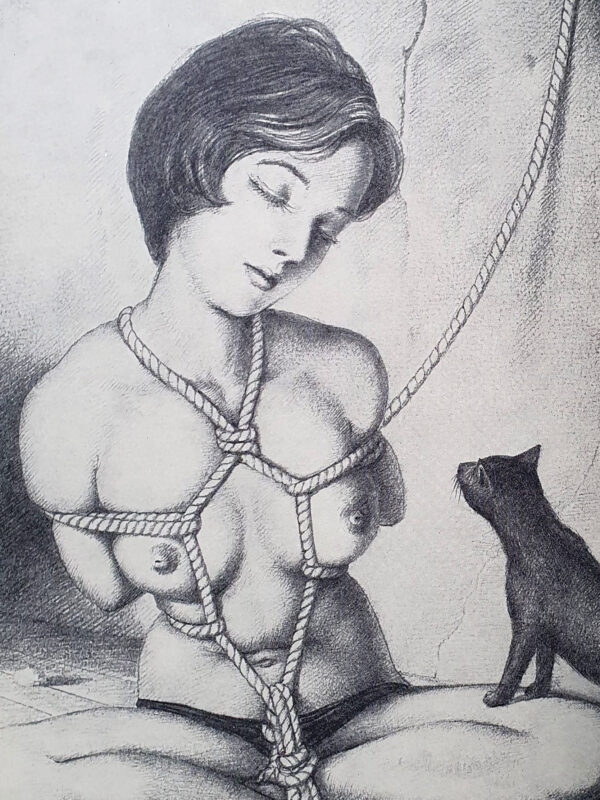

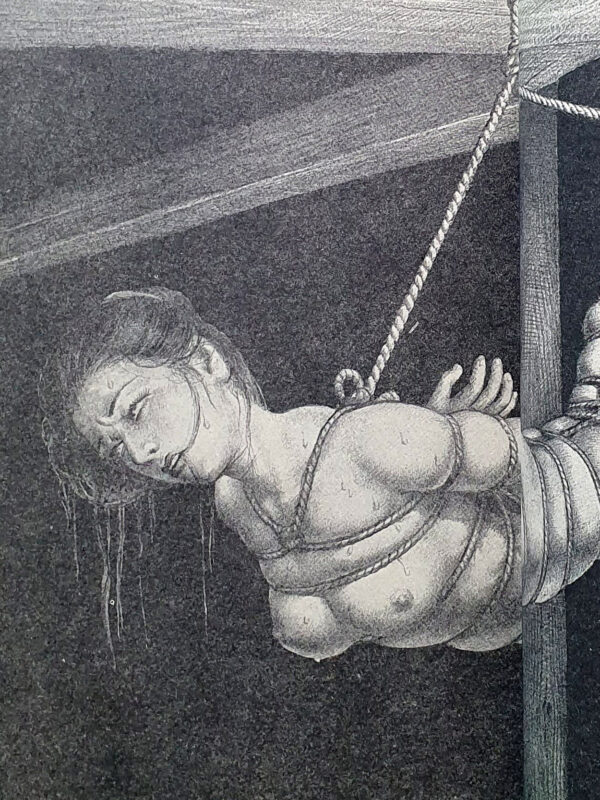

Under his direction, Gashū Nawa to Onna is not a simple collection of erotic illustrations. It functions as a visual argument. Rope is not an accessory to the female body, but a compositional force. It shapes posture, tension, and narrative space. The women depicted are neither passive decorations nor theatrical caricatures. They are framed as sites of constraint, endurance, and ambiguity.

The book’s success was immediate. A second edition was issued the following year, a rarity for such publications. It reflects both a limited initial print run and strong reception.

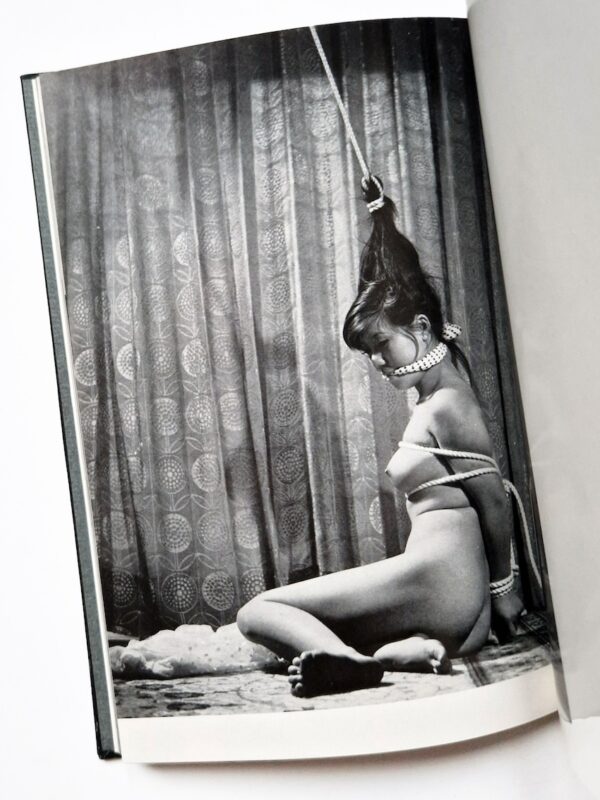

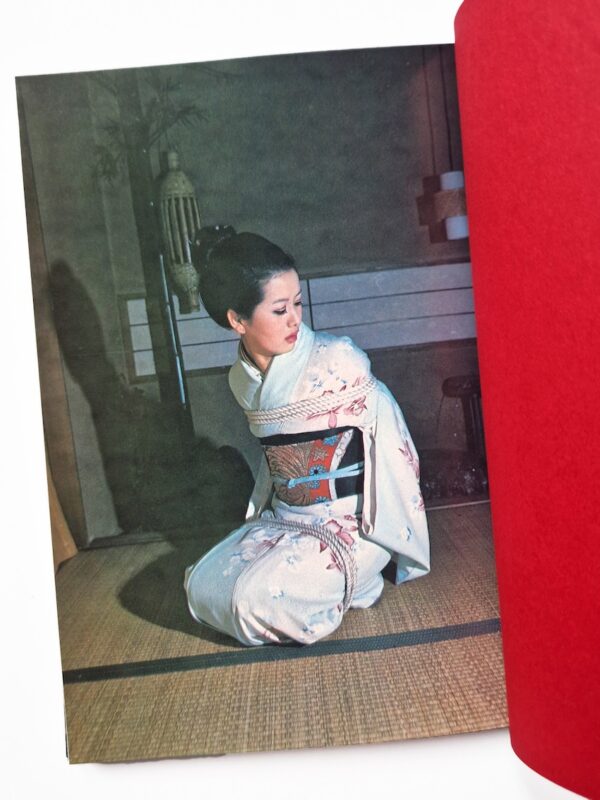

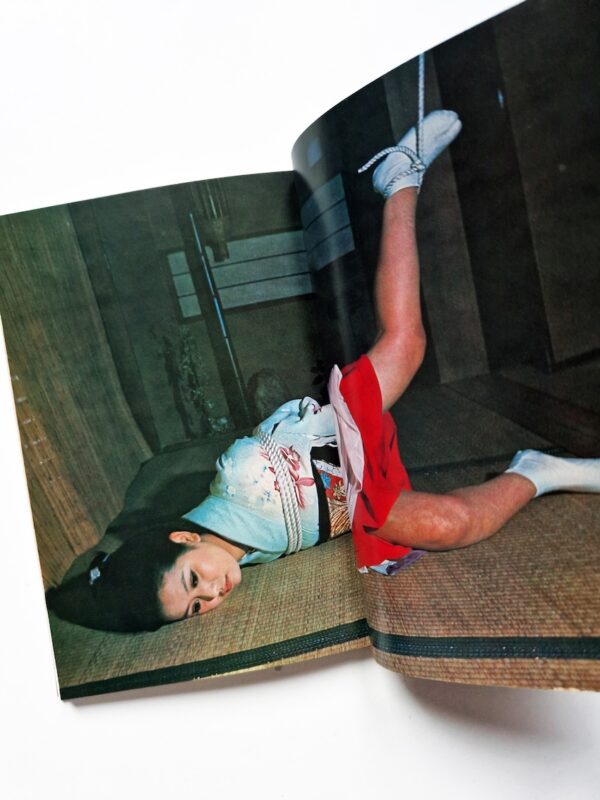

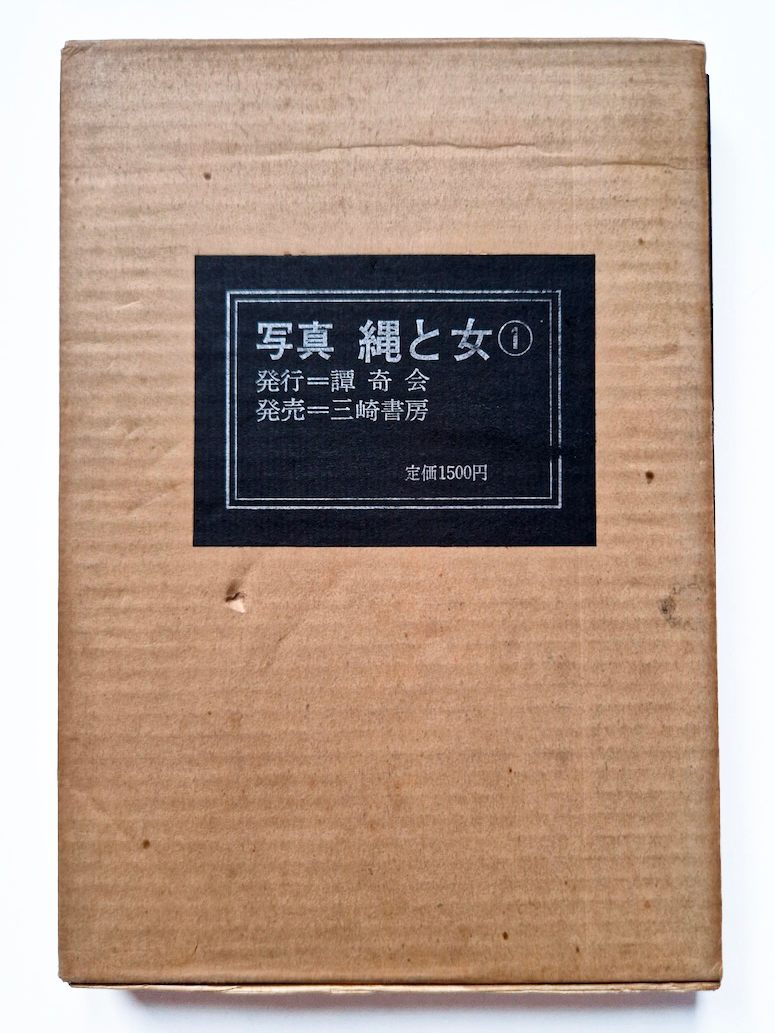

The Photographic Counterpart: Shashin Nawa to Onna 1 & 2

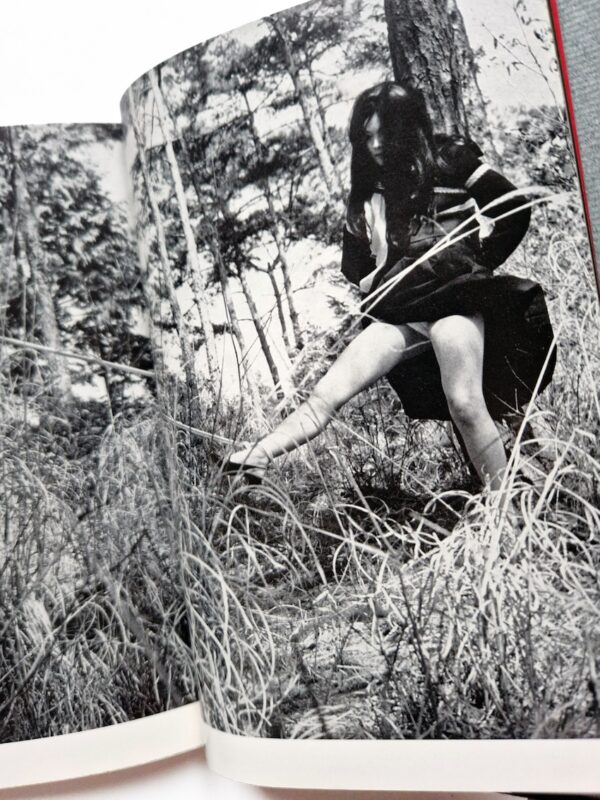

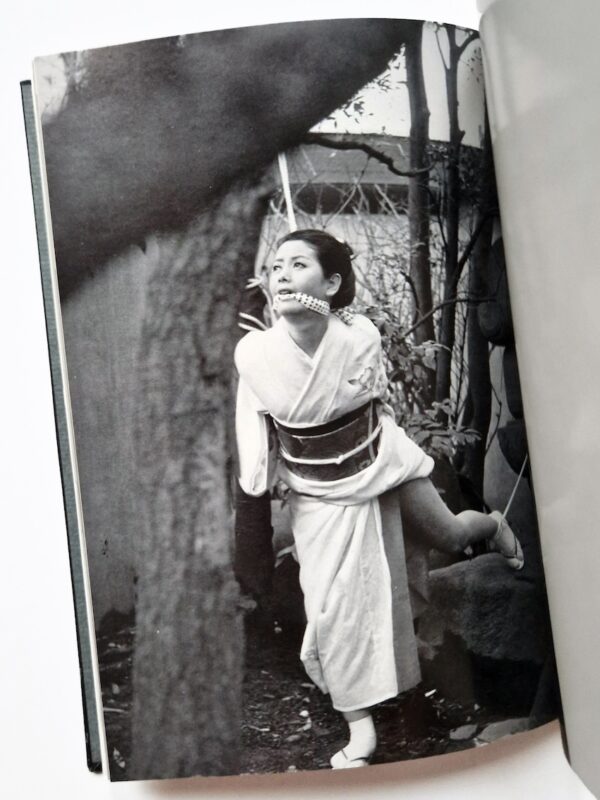

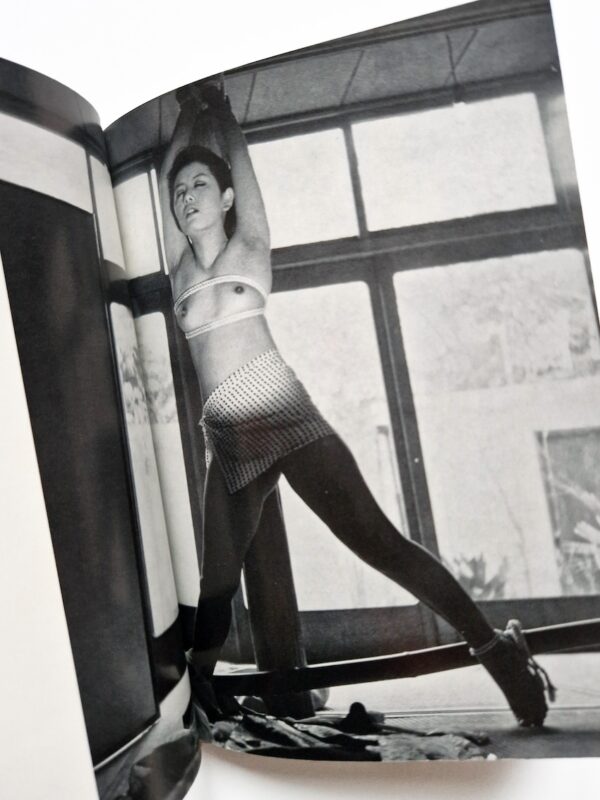

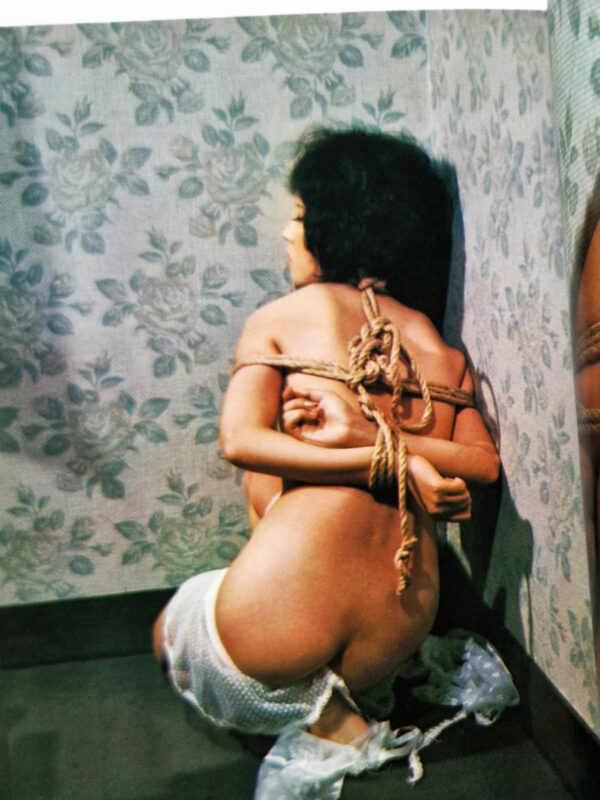

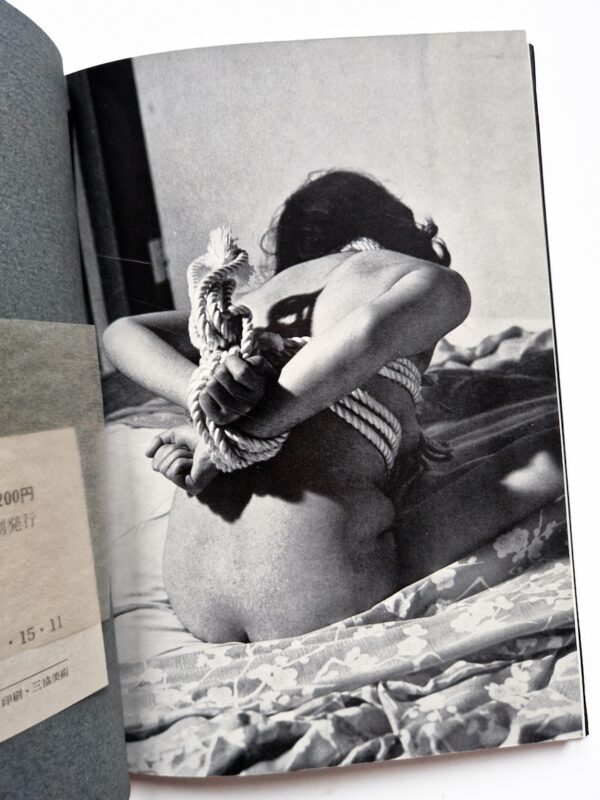

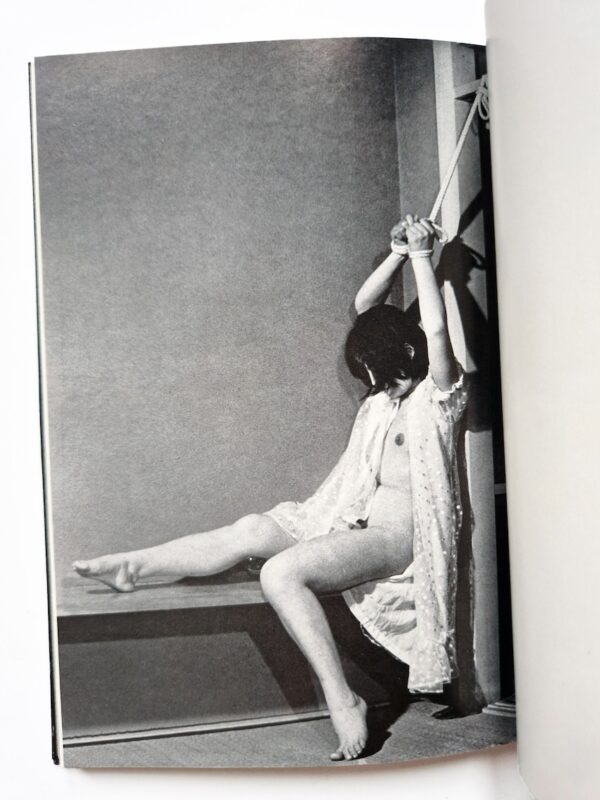

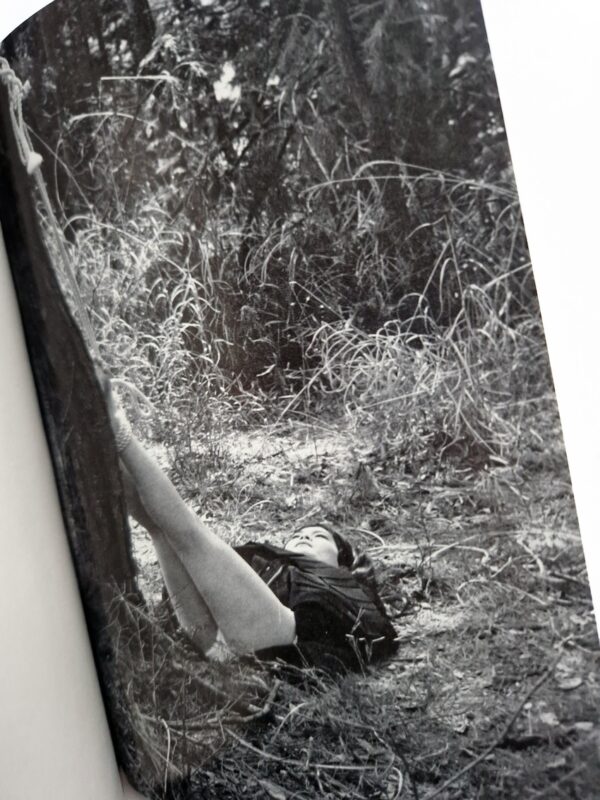

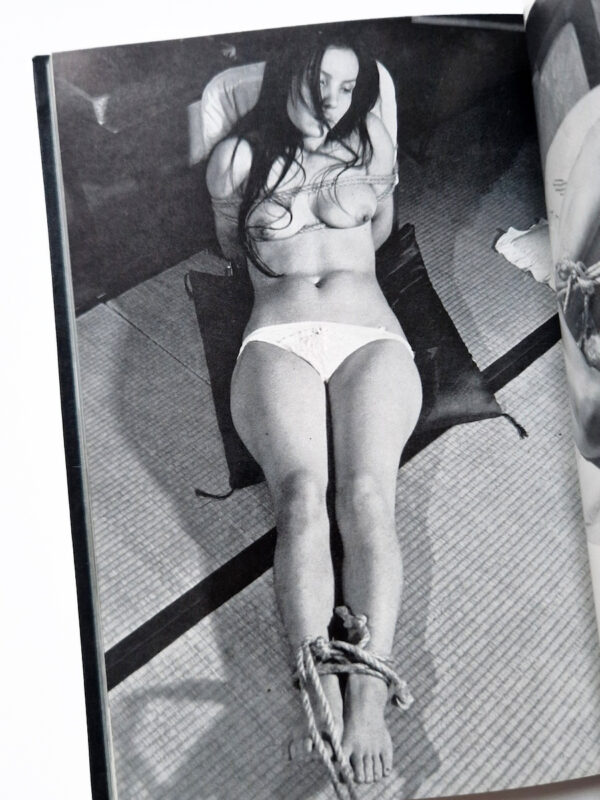

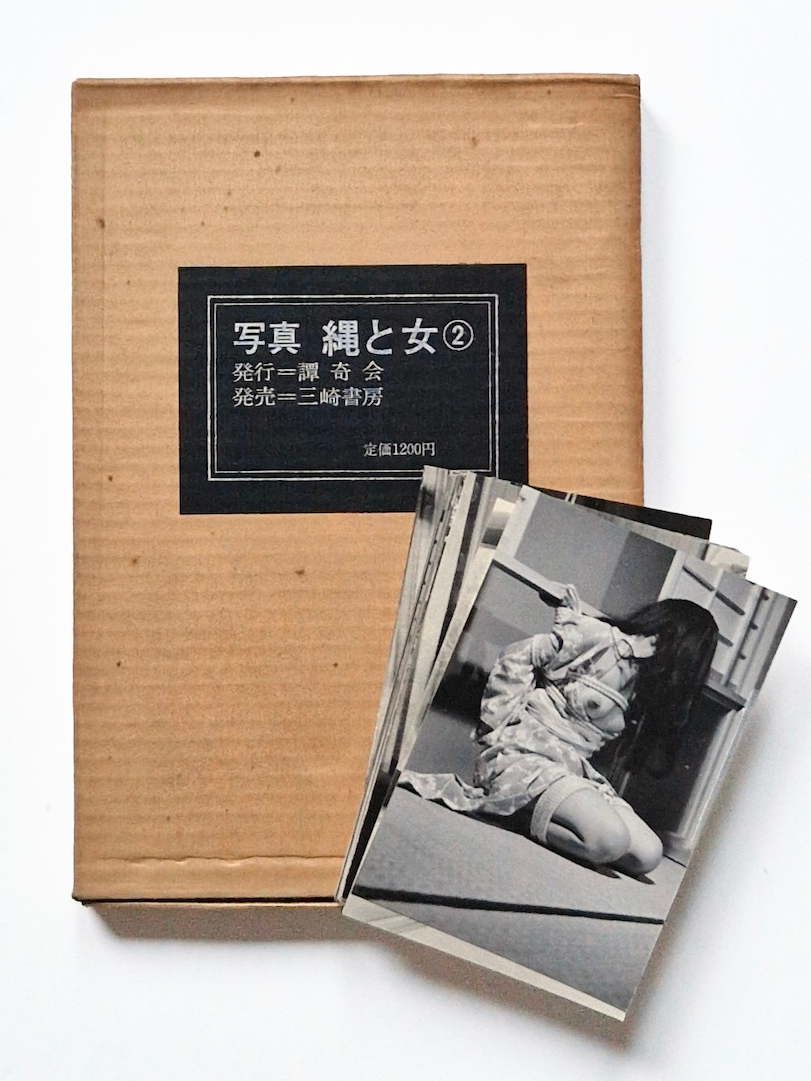

Released in the same year by the same publisher, 写真『縄と女』 Part 1 and Part 2 form the photographic counterpart to the illustrated volume.

These two books are edited — and the rope work executed — by Hiroshi Urado, a figure whose trajectory is crucial to understanding the trilogy as a whole.

Urado did not enter the SM world as a kinbakushi. He began his career as an editor, working at Kubo Shoten in the early 1960s and participating directly in the production of Uramado. Surrounded by key figures of the SM editorial scene, he absorbed its visual logic long before he ever touched a rope.

It was only at the end of the 1960s — through his proximity to Dan Oniroku and the activities of Oni Pro — that Urado began practicing kinbaku himself. What started as an editorial necessity quickly became a defining shift: the editor became a “rope man,” a term Urado preferred to the more formal title of kinbakushi.

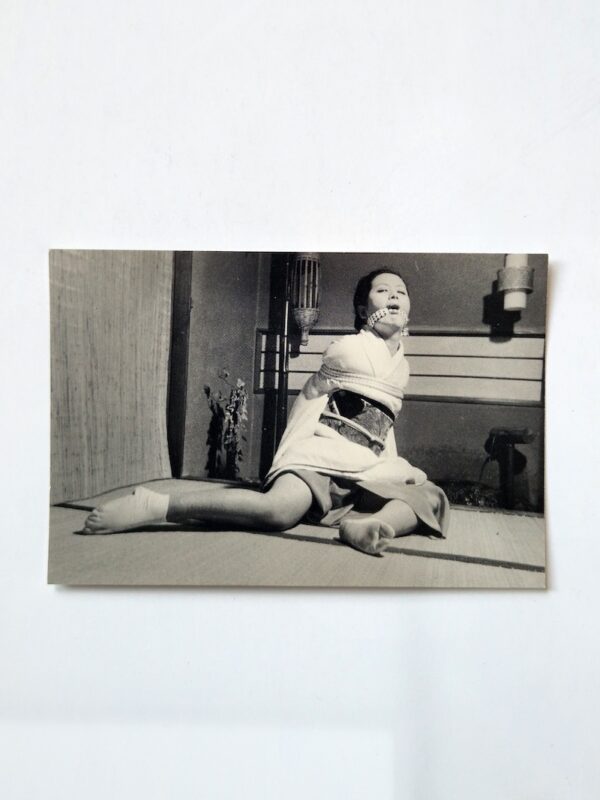

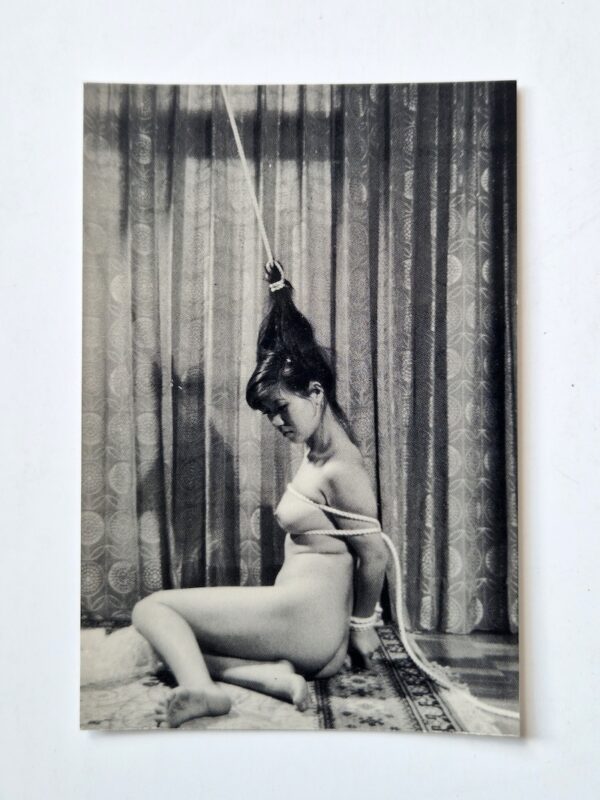

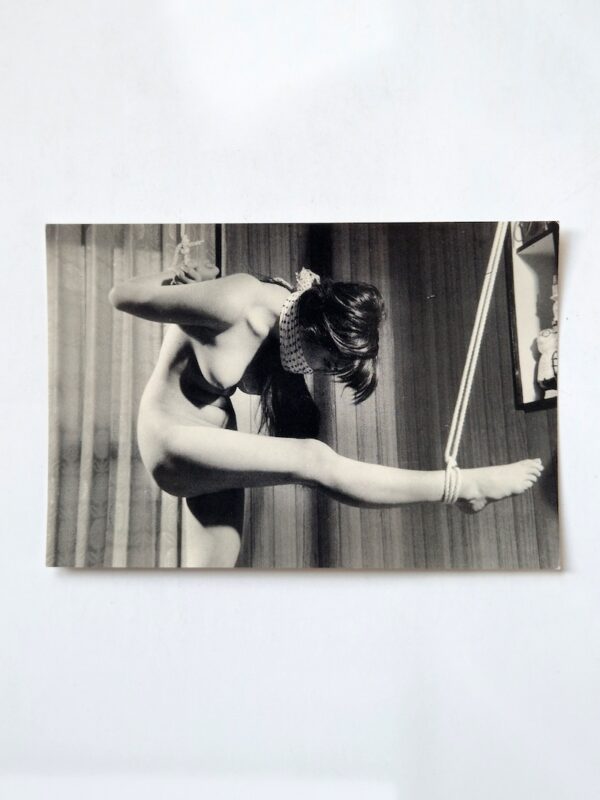

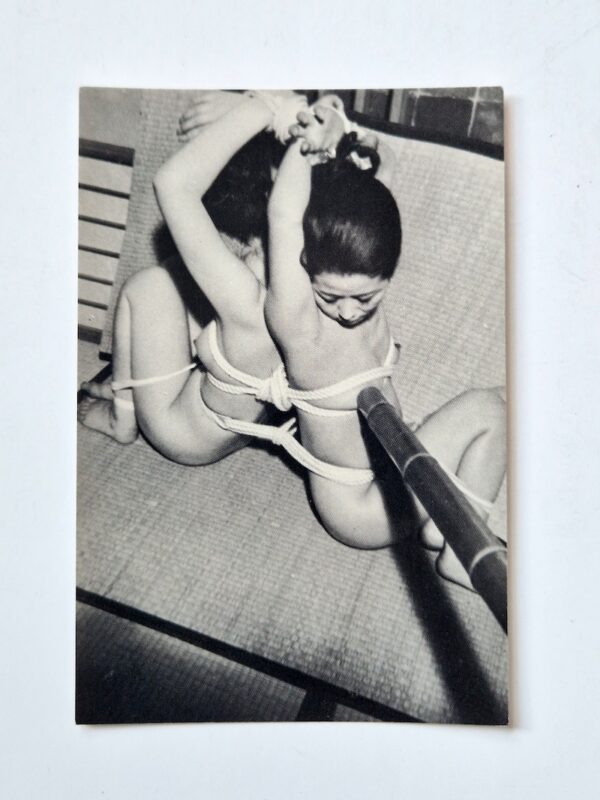

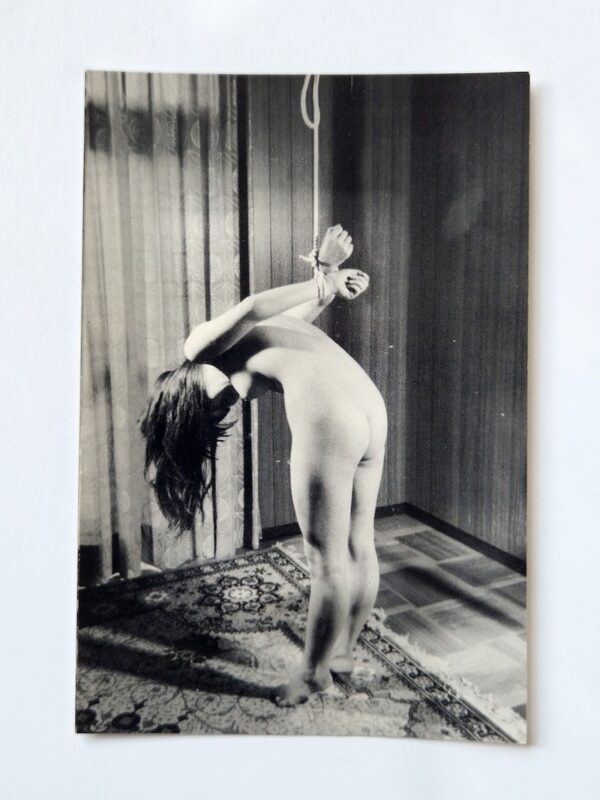

In Shashin Nawa to Onna, Urado’s approach is markedly different from the fantasy-driven stylization of illustration. The photographs emphasize physical presence, weight, gravity, and the direct relationship between rope and flesh. These volumes can be read as a pre-cinematic laboratory, anticipating the visual grammar Urado would soon bring to Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno SM films beginning with Flower and Snake in 1974.

One Title, Three Volumes, One Editorial Gesture

What binds these books together is not merely their shared title, format, or slipcase design — though these material similarities are striking — but a deeper editorial logic.

-

One illustrated volume articulates the imagined and symbolic dimension of rope.

-

Two photographic volumes assert its physical and performative reality.

-

One publisher, Misaki Shobo, provides the platform.

-

Two editors, Yoji Muku and Hiroshi Urado, emerge from the same SM editorial ecosystem, shaped by Uramado and its network.

There is no explicit documentation of direct collaboration between Muku and Urado on the books themselves. Yet their shared background, overlapping circles, and synchronized involvement in this project make coincidence highly unlikely. Nawa to Onna appears instead as the product of a collective cultural moment, when rope was being redefined — not as a marginal fetish, but as a visual and narrative capable of sustaining books, images, and eventually films.

From Page to Screen

In retrospect, the trilogy marks a threshold.

Within a few years, Urado would become one of the central rope figures in Japanese SM cinema (as Oniroku Dan Bakushi), supervising bondage for more than forty Nikkatsu productions. The visual logic explored in Shashin Nawa to Onna would migrate almost intact to the screen.

Meanwhile, the illustrated language consolidated in Gashū Nawa to Onna would remain a reference point — a testament to an era when illustration still played a central role in shaping erotic imagination, before photography and film fully took over.

Conclusion

Nawa to Onna is not simply a rare set of books.

It is a document of transition — from illustration to photography, from page to cinema, from editorial experiment to codified visual culture.

Seen together, the three volumes form one of the clearest snapshots of Japanese kinbaku at the moment it stepped into modernity.